Let’s proceed with previous topic (all of them from the Growth hacking checklist for FinTech) and consider today a legal part of Influencer marketing. Well, for FinTech Influencer marketing work all rules below.

Thus In the UK and the US appeared the rules. But common issue arises when there isn’t a monetary exchange or formal agreement between advertisers and influencers, but free products or ‘gifting’ are offered in exchange for content.

In the UK for instance if a brand has any level of input or editorial control over what an influencer posts ― this counts an advertisement and must comply with the local influencer code.

Meanwhile in Russia, authorities pay less attention to private social media accounts, content resulting from a gift, particularly when there are no formal obligations, is less likely to be scrutinised by local authorities.

What if you don’t comply?

Influencer marketing, especially FinTech Influencer marketing, both worldwide are under the same standards as traditional advertising, that means a lot of prohibitions and regulations. Important, extra scrutiny is imposed on influencer marketing for misleading and deceptive content.

Around the world, regulators increase fines for those who don’t make it clear that an ad has a commercial purpose or those who give misleading statements about a brand.

For instance a US-based supplement and nutrition brand “Teami’ has got a giant $15M fine for their influencer campaigns which didn’t properly disclose their paid partnerships additionally deceptively claiming their products could cause rapid and substantial weight loss.

Who is liable?

There are 3 parties who contribute to an influencer marketing post: the influencer, the company and the agencies that broker the agreement. Liable is all of them.

Last year the Swedish Consumer Ombudsman filed a lawsuit against an influencer, who had published advertising posts for a partner company.

Simultaneously, a lawsuit was filed against an agency that brokered the agreement, but not against the company whose products were being prompted.

The complaints included improper disclosure of advertisement content. The advertising labelling within the content did correspond local requirements so in the end the judgement was appealed.

Next example, the FTC has filed a number of lawsuits for inadequate labelling of posts. In these cases the companies bear the majority of the heat but the agencies didn’t face scrutiny.

What counts as an ad?

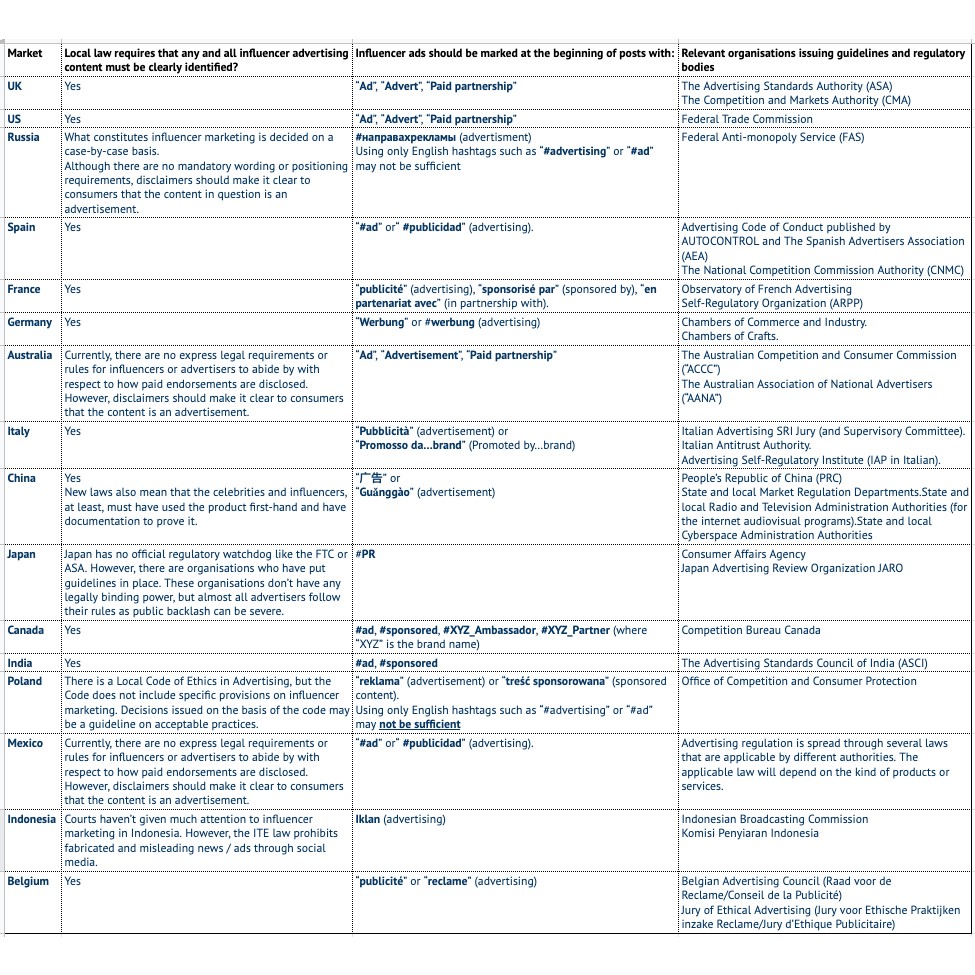

Before pushing content live, local research should be done due to different countries have different codes of practice. The spreadsheet in the next photo helps to highlight the basic requirements in different countries.

Requirements for different social platforms i.e Youtube, Instagram were not mentioned, but for example Instagram has a ‘paid partnership’ feature.

One point was clear throughout: regulators are seriously cracking down on influencer marketing. Whilst disclosure is currently the focus of most court cases and almost seems like ‘old news’ now, there are undoubtedly more developments to come. The same story is for using children as influencers.

How to work with influencers?

The key recommendations when working with influencers are: content should adhere to local and traditional advertising laws.

At second, an average person ― one not familiar with influencer marketing or sponsored content ― needs to understand that there’s a commercial connection between the influencer and the company and if in fact, it is a paid-for partnership.

The growing success of influencer advertising in social media has drawn the attention of both the public and watchdogs. Both demographic groups of late adopters to social media now fully comprehend its appeal as well as risks.